State returns shooting range grant to feds

Friday, September 19, 2003

HUD cites pattern of suspicious data used to support nine grants awarded under Janklow.

By Denise Ross, Journal Staff Writer

The state of South Dakota will cancel $511,200 in federal grant money it awarded in December to a shooting range planned for northeast of Sturgis and will repay the federal government $313,800 already spent on the project, according to a Thursday letter.

South Dakota's Tourism and State Development secretary John Calvin sent the letter to a HUD official in Denver in response to a HUD investigation that found demographic data used by the state to support the shooting range grant and nine others differed significantly from U.S. census data.

In their report to the state, HUD officials note they have the authority to withhold future grant money if they aren't satisfied with the state's response to the 74-page report issued Aug. 18.

The state's plan to cancel and repay the shooting range grant, totaling $825,000, will require HUD approval before it is final. HUD officials in Denver did not return a telephone call from the Rapid City Journal on Thursday.

Former Gov. Bill Janklow, now South Dakota's congressman, awarded each of the grants now in question under HUD's Community Development Block Grant program. Under the CDBG program, units of local government receive chunks of federal money and have discretion in awarding grants to projects that meet criteria set forth by the federal government. In South Dakota, all CDBG money goes through the state except the grants awarded in Rapid City and Sioux Falls, where the cities distribute grants.

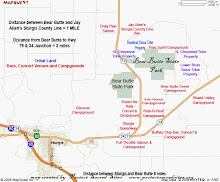

What the state's decision to cancel the shooting range grant means for the future of the project was unclear Thursday. Organizers had planned to use only $75,000 in local funding for the $900,000 project. The nonprofit Black Hills Sportsmen's Complex had planned to operate the shooting range, already the subject of two lawsuits, at a site four miles north of Bear Butte State Park.

Sturgis Mayor Mark Ziegler said he could not comment on the shooting range because of ongoing litigation.

One of the lawsuits, filed against HUD in April by a group of Sturgis residents, made the allegation that the shooting range would not benefit low- and moderate-income people as required by CDBG criteria. Federal rules require that grants go to projects that would benefit a geographic area where at least 51 percent of the population is low- or moderate-income.

A second lawsuit, filed in February, contends that the state failed to consult with American Indian tribes about the shooting range's impact on Bear Butte, a site sacred to a number of tribes. The judge in that case on Thursday postponed indefinitely a Nov. 4 trial date, noting that the state's move to cancel the grant could end the project.

HUD investigated the shooting range grant and a series of grants awarded from the $8.5 million worth of South Dakota's 2002 CDBG cycle. HUD found a pattern in which the state consistently used low- and moderate- income data that exceeded existing census data by double-digit percentages.

In the case of the shooting range grant, U.S. census data showed that 42.5 percent of Sturgis residents meet that definition. In contrast, a telephone survey used to support the grant showed that 56.1 percent of the people in Sturgis meet that definition.

"There is a consistent pattern of survey results showing a significantly higher percentage of low- and moderate- income persons than Census data," the HUD report says. "The difference between the survey data and both 1990 and 2000 Census data often exceeds 10 percent. In one egregious case, the difference is more than 20 percent."

HUD found that when census data already showed an area met CDBG guidelines, the census data was used to support the grant, and no survey was done.

Communities where a survey showed a different percentage of low- and moderate-income people from the 2000 Census are listed below.

-- Aberdeen � Census, 41.1 percent; survey, 52 percent.

-- Avon � Census, 40.6 percent; survey, 56.36 percent.

-- Corsica � Census, 41.2 percent; survey, 56.36 percent.

-- Iroquois � Census, 49.1 percent; survey, 56.17 percent.

-- DeSmet � Census, 42 percent; survey, 51.05 percent.

-- Beresford � Census, 45.2 percent; survey, 54.9 percent.

-- Mobridge � Census, 51.2 percent; survey, 52 percent.

-- Minnehaha County � Census, 30.9 percent; survey, 64 percent.

-- Black Hawk Sanitary District � Census, no data; survey, 52.9 percent.

Also, HUD found that the state repeatedly did not clearly identify the geographic area that would benefit from a given grant. HUD also found that sometimes one geographic area was identified as the area that would benefit, but data from a different geographic area was cited when listing the criteria.

State of South Dakota officials have 45 days from the Aug. 18 report to respond to HUD's findings. If HUD and the state are unable to agree on what should be done, HUD rules allow the agency to take one of six different actions. Those include issuing a letter of reprimand, canceling future block grants to the state and instituting a policy of releasing grant funds only after HUD officials approve the projects in question.

Contact Denise Ross at 394-8438 or denise.ross@rapidcityjournal.com

http://www.rapidcityjournal.com/articles/2003/09/19/news/local/top/news01.txt

Friday, September 19, 2003

Wednesday, March 19, 2003

Future of shooting range goes before federal judge

Future of shooting range goes before federal judge

By Bill Cissell, Journal Staff Writer Wednesday, March 19, 2003

RAPID CITY � The future of a shooting range north of Sturgis is in the hands of a federal judge.

A hearing on a preliminary injunction to temporarily stop any further work on the project is set for 9 a.m. Monday, March 24, before U.S. District Judge Karen Schreier.

The judge also set 9 a.m. June 30 as the hearing date for a permanent injunction on the shooting range.

Construction has not begun; plans for the range are still in the design stage.

Five American Indian tribes � Northern Cheyenne, Rosebud Sioux, Yankton Sioux, Crow Creek Sioux and Standing Rock Sioux � filed a motion requesting the injunction.

They said noise from the Black Hills Sportsman's Complex, which is planned for more than four miles north of Bear Butte, will interfere with religious ceremonies at the butte, which is considered sacred by many Plains Indians. A grassroots organization called Defenders of the Black Hills also joined in the action.

The injunction request names as defendants Mel Martinez, U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development, the Black Hills Council of Local Governments, Sturgis Industrial Expansion Corp., city of Sturgis and Black Hills Sportsman's Complex.

The tribes also say they weren't contacted about the proposal, which they say is mandated by federal law.

The shooting complex would have pistol, rifle and archery ranges, as well as a place for law enforcement officials to practice and youth organizations to learn shooting safety.

Organizers said the range also gives local gun and ammunition manufacturers a place to test and demonstrate new products.

On March 17, in a telephone conference call that included attorneys for all those involved and Schreier, range developers agreed "to not proceed with plans but continue the planning process."

They said they hoped to have the facility in operation this summer.

Money for the almost $1 million project came primarily from an $850,000 federal community development block grant.

Local organizers were required to raise $75,000.

In an Oct. 17, 2002, letter to Black Hills Council of Local Governments executive director Van Lindquist, the National Park Service suggested that "the Black Hills Council of Local Governments conduct a gunfire test and invite the interested parties ... to experience the sound levels from Bear Butte."

Black Hills Council provides administrative and technical support to a variety of local governments. It was in charge of shepherding the grant through the approval process.

In a subsequent letter to Don Kilman of the Office of Federal Agency Programs, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Lindquist said a live test couldn't be done because the range, with all of its planned noise baffles and berms, would have to be built in order to have a good demonstration.

In the same letter, Lindquist said that during a Sept. 11, 2002, meeting of representatives of the state's historic preservation office, block grant officials and the Black Hills Council, it was agreed that getting approval from the Tribal Government Relation Office would fulfill the requirement to contact Indian tribes.

The site, 13 miles north of Sturgis and east off of Highway 79, is the second location planned.

The first, about 11 miles east of Sturgis on Alkali Road, was rejected after it came under fire from adjacent landowners.

Contact Bill Cissell at 394-8412 or e-mail bill.cissell@rapidcityjournal.com

http://www.rapidcityjournal.com/articles/2003/03/19/news/local/news07.txt

By Bill Cissell, Journal Staff Writer Wednesday, March 19, 2003

RAPID CITY � The future of a shooting range north of Sturgis is in the hands of a federal judge.

A hearing on a preliminary injunction to temporarily stop any further work on the project is set for 9 a.m. Monday, March 24, before U.S. District Judge Karen Schreier.

The judge also set 9 a.m. June 30 as the hearing date for a permanent injunction on the shooting range.

Construction has not begun; plans for the range are still in the design stage.

Five American Indian tribes � Northern Cheyenne, Rosebud Sioux, Yankton Sioux, Crow Creek Sioux and Standing Rock Sioux � filed a motion requesting the injunction.

They said noise from the Black Hills Sportsman's Complex, which is planned for more than four miles north of Bear Butte, will interfere with religious ceremonies at the butte, which is considered sacred by many Plains Indians. A grassroots organization called Defenders of the Black Hills also joined in the action.

The injunction request names as defendants Mel Martinez, U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development, the Black Hills Council of Local Governments, Sturgis Industrial Expansion Corp., city of Sturgis and Black Hills Sportsman's Complex.

The tribes also say they weren't contacted about the proposal, which they say is mandated by federal law.

The shooting complex would have pistol, rifle and archery ranges, as well as a place for law enforcement officials to practice and youth organizations to learn shooting safety.

Organizers said the range also gives local gun and ammunition manufacturers a place to test and demonstrate new products.

On March 17, in a telephone conference call that included attorneys for all those involved and Schreier, range developers agreed "to not proceed with plans but continue the planning process."

They said they hoped to have the facility in operation this summer.

Money for the almost $1 million project came primarily from an $850,000 federal community development block grant.

Local organizers were required to raise $75,000.

In an Oct. 17, 2002, letter to Black Hills Council of Local Governments executive director Van Lindquist, the National Park Service suggested that "the Black Hills Council of Local Governments conduct a gunfire test and invite the interested parties ... to experience the sound levels from Bear Butte."

Black Hills Council provides administrative and technical support to a variety of local governments. It was in charge of shepherding the grant through the approval process.

In a subsequent letter to Don Kilman of the Office of Federal Agency Programs, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Lindquist said a live test couldn't be done because the range, with all of its planned noise baffles and berms, would have to be built in order to have a good demonstration.

In the same letter, Lindquist said that during a Sept. 11, 2002, meeting of representatives of the state's historic preservation office, block grant officials and the Black Hills Council, it was agreed that getting approval from the Tribal Government Relation Office would fulfill the requirement to contact Indian tribes.

The site, 13 miles north of Sturgis and east off of Highway 79, is the second location planned.

The first, about 11 miles east of Sturgis on Alkali Road, was rejected after it came under fire from adjacent landowners.

Contact Bill Cissell at 394-8412 or e-mail bill.cissell@rapidcityjournal.com

http://www.rapidcityjournal.com/articles/2003/03/19/news/local/news07.txt

Tuesday, March 4, 2003

Tribes ask court to stop range

Tribes ask court to stop range

By Bill Cissell, Journal Staff Writer Tuesday, March 04, 2003

RAPID CITY

Four American Indian tribes and a volunteer organization composed primarily of Indian people want the federal court to stop construction of a shooting range north of Sturgis and Bear Butte.

The Northern Cheyenne, Rosebud Sioux, Crow Creek Sioux and Yankton Sioux tribes and Defenders of the Black Hills filed a motion Friday in U.S. District Court in Rapid City for a preliminary injunction to stop the spending of federal dollars on the Black Hills Sportsman's Complex.

Named in the suit as defendants are U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Mel Martinez, Black Hills Council of Local Governments, Sturgis Industrial Expansion Corp., the city of Sturgis and Black Hills Sportsman's Complex.

The noise from the range, about four miles north of Bear Butte, will be a distraction to tribal ceremonies, according to court documents. The tribes also claim they should have been part of the planning process and didn't know anything about the shooting range until former Gov. Bill Janklow approved it late last year.

Proponents of the facility say the range will provide a much-needed practice and training area for shooting organizations, local law enforcement officials and others. The Black Hills is also home to almost a dozen gun- and ammunition-manufacturing businesses that could use the range to test and demonstrate new products.

Complex officials said they would have no comment on the issue because it is now in court.

Charmaine White Face, a spokeswoman for Defenders of the Black Hills, said she didn't know when the court might act but said there is a request for the court to act quickly.

Contact Bill Cissell at 394-8412 or bill.cissell@rapidcityjournal.com

http://www.rapidcityjournal.com/articles/2003/03/04/news/local/news05.txt

By Bill Cissell, Journal Staff Writer Tuesday, March 04, 2003

RAPID CITY

Four American Indian tribes and a volunteer organization composed primarily of Indian people want the federal court to stop construction of a shooting range north of Sturgis and Bear Butte.

The Northern Cheyenne, Rosebud Sioux, Crow Creek Sioux and Yankton Sioux tribes and Defenders of the Black Hills filed a motion Friday in U.S. District Court in Rapid City for a preliminary injunction to stop the spending of federal dollars on the Black Hills Sportsman's Complex.

Named in the suit as defendants are U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Mel Martinez, Black Hills Council of Local Governments, Sturgis Industrial Expansion Corp., the city of Sturgis and Black Hills Sportsman's Complex.

The noise from the range, about four miles north of Bear Butte, will be a distraction to tribal ceremonies, according to court documents. The tribes also claim they should have been part of the planning process and didn't know anything about the shooting range until former Gov. Bill Janklow approved it late last year.

Proponents of the facility say the range will provide a much-needed practice and training area for shooting organizations, local law enforcement officials and others. The Black Hills is also home to almost a dozen gun- and ammunition-manufacturing businesses that could use the range to test and demonstrate new products.

Complex officials said they would have no comment on the issue because it is now in court.

Charmaine White Face, a spokeswoman for Defenders of the Black Hills, said she didn't know when the court might act but said there is a request for the court to act quickly.

Contact Bill Cissell at 394-8412 or bill.cissell@rapidcityjournal.com

http://www.rapidcityjournal.com/articles/2003/03/04/news/local/news05.txt

Monday, February 24, 2003

Bear Butte threatened by shooting range

Bear Butte threatened by shooting range Email this page Print this page

Posted: February 24, 2003

by: Suzan Shown Harjo / Indian Country Today

In the Tsistsistas language of the Cheyenne Nation, Bear Butte is Nowahwus, Holy Mountain. In 50 other Native languages, it is called sacred ground, a place of peace and sanctuary.

Native people go to this honored place to pray, to commemorate events and persons, to seek spiritual wisdom and guidance, to renew traditions and sacred objects, to mark passages of life and to make pilgrimages and offerings.

Holy Mountain rises 1,400 feet above the prairies of the Great Plains, just beyond the northern tip of the Black Hills. It is a National Historic Landmark in the Bear Butte State Park on the South Dakota side of the border with Wyoming.

Eagles and hawks calling from the mountaintop can be heard from great distances. Those are the loudest sounds in the area, if you don't count the week every August when 400,000 bikers descend on the town of Sturgis, S.D., some ten miles from Bear Butte.

The tranquility of Holy Mountain is about to be shattered by 10,000 gunshot rounds daily, if private investors get the shooting range and sports complex they have been developing in secret for more than a year.

Well, not really in secret. The mayor of Sturgis, Mark Ziegler, knew about it a year ago. He says Rep. William J. Janklow, R-S.D., who was then the state's governor, brought the project to his attention.

The federal housing department knew about it and ponied up a $250,000 community development starter grant last year. The Black Hills Council of Local Governments knew about it. They got the quarter-million dollars.

The only ones who weren't in on the secret were the tribal governments who own property at Bear Butte and the Indian people who pray there.

The developers, the state and the feds ignored a whole lot of laws when they failed to consult with or even inform those tribal and traditional religious leaders with proprietary, environmental, cultural and religious interests in Bear Butte.

From time immemorial, Cheyenne, Lakota, Arapaho, Kiowa, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and other people have gone to Bear Butte for religious purposes.

Long before Europeans came to our countries to escape religious persecution in their homelands, Bear Butte was a center of religious freedom.

In all the traditions and histories of those with millennial experience at Bear Butte, there is no record of a hostile encounter or argument. None, that is, until the U.S. Army and federal Indian Police were dispatched in the late 1800s to capture or kill Indians who tried to go there.

Under the federal "Civilization Regulations" from the 1880s to the 1930s, traditional religious practices were banned and people who tried to go to sacred places to pray were punished severely and even marked for death. Most sacred places were declared part of the public domain and later divided up among the federal agencies, states, miners and other non-Indian squatters.

That is how the Bear Butte Indian lands ended up in state and private non-Indian hands.

Boosters of the shooting project say its rifle, pistol and skeet ranges will not affect Bear Butte because it will be located four miles from the mountain.

Existing plans call for testing by the gun industry, but the caliber and decibel level of the weapons to be tested are not specified. Because no environmental impact study has been conducted, the effect of the project on the air quality and serenity of Bear Butte is not known.

The impact of the project on people praying, eagles nesting or buffalo grazing at the base of Bear Butte has not been studied.

There has been no objective scrutiny of the plans for the entire sports complex, with its proposed clubhouse, restaurant and motel. At the very least, they will significantly increase water usage in the area at a time when local sprawl and development are drying up the springs and medicine plants at Bear Butte.

This decrease in water also is a contributing factor to the current condition of soil erosion at Bear Butte. In 1996, a large fire consumed most of the trees and underbrush along one face of the mountain. Even though young trees are growing now, there is not enough moisture or plant life to stop the soil from wearing away.

Bear Butte is more of a mountain than a butte. It's a volcano that bubbled up and bulged the earth's surface, but never erupted. It's on the east end of a spine of volcanoes extending 60 miles west to Devil's Tower, which can be seen from the top of the mountain.

In 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer rode his horse to the top of Bear Butte. In this place of prayer and contemplation where everyone walks gently and whispers, Custer's bombast could not have endeared him to any Indian people praying on Holy Mountain that day.

Cheyenne people at Bear Butte would have known of Custer from his campaigns against their relatives in what is now Oklahoma, particularly at the Washita Massacre of Cheyenne Peace Chief Black Kettle and his people.

Lakota people at Bear Butte would have known of Custer from his campaigns against their relatives. Custer was despised as the person who triggered the gold rush and massive desecration of the Black Hills.

Within two years after Custer's defilement of Bear Butte, he was killed by Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Both in life and in death, Custer ushered in the era of official sacrilege of Indian sacred places and criminalization of traditional Indian people.

A Sturgis historian and former Rapid City Journal reporter, Bob Lee, wrote an opinion piece for that newspaper in mid-Feb., "No one opposed early firing range." Citing his own writings as his authoritative source on Indian history and religion - and getting much of the story wrong in the process - he peddles a tale that "present-day Indian activists are voicing grievances that didn't exist with their ancestors."

Lee claims that Fort Meade, just east of Sturgis, operated a firing range throughout its 66-year history "even closer to Bear Butte without complaint" from Indian people. Fort Meade was established in 1878 as a 7th Cavalry post to protect prospectors from the Indians. Lee fails to mention that Custer was the fort's first commander and that Indians were the targets of the "firing range."

Lee makes much of the "55 Indian soldiers" who were stationed at Fort Meade and "used the fort's firing range without complaint of its proximity to Bear Butte."

This point is "absurd," said noted historian and attorney Vine Deloria Jr.

Deloria, who is Standing Rock Sioux and the author of more than two dozen books, said: "People serving in a foreign army are hardly the spiritual leaders of a country."

Lee claims that Bear Butte wasn't sacred to the Lakota "until after the butte was established as a state park in 1962." This is untrue, as historians worth their salt know and have documented, and as representatives of the Cheyenne River, Oglala and other Sioux tribes have been saying clearly and publicly in connection with the proposed shooting range.

He falsely claims that the Cheyenne "religion originated there." Tsistsistas Prophet Sweet Medicine received visions, medicines and instructions at Bear Butte that dramatically changed societal and ceremonial order, but Cheyenne religion existed for thousands of years before that time.

Lee also misperceives the history that is unfolding now, wrongly stating that "no objections to the proposed firing range in the vicinity of Bear Butte have come from the Cheyenne, who have been making pilgrimages to their sacred shrine for generations." Cheyenne leaders are clearly saying that the shooting range project would impede religious freedom and other rights.

Holy Mountain has been standing for more than 500 million years. It has taken the white man a little over a century to bring her to this point of endangerment. For more than 50 of those years, the federal government tried, but failed, to keep Indians away from Bear Butte. Today, it seems that developers and government agents are trying to take the mountain away from the Indians.

Bear Butte is strong and they will fail in this, too.

Suzan Shown Harjo, Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee, is president of the Morning Star Institute in Washington, D.C., and a columnist for Indian Country Today.

http://www.indiancountry.com/content.cfm?id=1046104233

Posted: February 24, 2003

by: Suzan Shown Harjo / Indian Country Today

In the Tsistsistas language of the Cheyenne Nation, Bear Butte is Nowahwus, Holy Mountain. In 50 other Native languages, it is called sacred ground, a place of peace and sanctuary.

Native people go to this honored place to pray, to commemorate events and persons, to seek spiritual wisdom and guidance, to renew traditions and sacred objects, to mark passages of life and to make pilgrimages and offerings.

Holy Mountain rises 1,400 feet above the prairies of the Great Plains, just beyond the northern tip of the Black Hills. It is a National Historic Landmark in the Bear Butte State Park on the South Dakota side of the border with Wyoming.

Eagles and hawks calling from the mountaintop can be heard from great distances. Those are the loudest sounds in the area, if you don't count the week every August when 400,000 bikers descend on the town of Sturgis, S.D., some ten miles from Bear Butte.

The tranquility of Holy Mountain is about to be shattered by 10,000 gunshot rounds daily, if private investors get the shooting range and sports complex they have been developing in secret for more than a year.

Well, not really in secret. The mayor of Sturgis, Mark Ziegler, knew about it a year ago. He says Rep. William J. Janklow, R-S.D., who was then the state's governor, brought the project to his attention.

The federal housing department knew about it and ponied up a $250,000 community development starter grant last year. The Black Hills Council of Local Governments knew about it. They got the quarter-million dollars.

The only ones who weren't in on the secret were the tribal governments who own property at Bear Butte and the Indian people who pray there.

The developers, the state and the feds ignored a whole lot of laws when they failed to consult with or even inform those tribal and traditional religious leaders with proprietary, environmental, cultural and religious interests in Bear Butte.

From time immemorial, Cheyenne, Lakota, Arapaho, Kiowa, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and other people have gone to Bear Butte for religious purposes.

Long before Europeans came to our countries to escape religious persecution in their homelands, Bear Butte was a center of religious freedom.

In all the traditions and histories of those with millennial experience at Bear Butte, there is no record of a hostile encounter or argument. None, that is, until the U.S. Army and federal Indian Police were dispatched in the late 1800s to capture or kill Indians who tried to go there.

Under the federal "Civilization Regulations" from the 1880s to the 1930s, traditional religious practices were banned and people who tried to go to sacred places to pray were punished severely and even marked for death. Most sacred places were declared part of the public domain and later divided up among the federal agencies, states, miners and other non-Indian squatters.

That is how the Bear Butte Indian lands ended up in state and private non-Indian hands.

Boosters of the shooting project say its rifle, pistol and skeet ranges will not affect Bear Butte because it will be located four miles from the mountain.

Existing plans call for testing by the gun industry, but the caliber and decibel level of the weapons to be tested are not specified. Because no environmental impact study has been conducted, the effect of the project on the air quality and serenity of Bear Butte is not known.

The impact of the project on people praying, eagles nesting or buffalo grazing at the base of Bear Butte has not been studied.

There has been no objective scrutiny of the plans for the entire sports complex, with its proposed clubhouse, restaurant and motel. At the very least, they will significantly increase water usage in the area at a time when local sprawl and development are drying up the springs and medicine plants at Bear Butte.

This decrease in water also is a contributing factor to the current condition of soil erosion at Bear Butte. In 1996, a large fire consumed most of the trees and underbrush along one face of the mountain. Even though young trees are growing now, there is not enough moisture or plant life to stop the soil from wearing away.

Bear Butte is more of a mountain than a butte. It's a volcano that bubbled up and bulged the earth's surface, but never erupted. It's on the east end of a spine of volcanoes extending 60 miles west to Devil's Tower, which can be seen from the top of the mountain.

In 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer rode his horse to the top of Bear Butte. In this place of prayer and contemplation where everyone walks gently and whispers, Custer's bombast could not have endeared him to any Indian people praying on Holy Mountain that day.

Cheyenne people at Bear Butte would have known of Custer from his campaigns against their relatives in what is now Oklahoma, particularly at the Washita Massacre of Cheyenne Peace Chief Black Kettle and his people.

Lakota people at Bear Butte would have known of Custer from his campaigns against their relatives. Custer was despised as the person who triggered the gold rush and massive desecration of the Black Hills.

Within two years after Custer's defilement of Bear Butte, he was killed by Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Both in life and in death, Custer ushered in the era of official sacrilege of Indian sacred places and criminalization of traditional Indian people.

A Sturgis historian and former Rapid City Journal reporter, Bob Lee, wrote an opinion piece for that newspaper in mid-Feb., "No one opposed early firing range." Citing his own writings as his authoritative source on Indian history and religion - and getting much of the story wrong in the process - he peddles a tale that "present-day Indian activists are voicing grievances that didn't exist with their ancestors."

Lee claims that Fort Meade, just east of Sturgis, operated a firing range throughout its 66-year history "even closer to Bear Butte without complaint" from Indian people. Fort Meade was established in 1878 as a 7th Cavalry post to protect prospectors from the Indians. Lee fails to mention that Custer was the fort's first commander and that Indians were the targets of the "firing range."

Lee makes much of the "55 Indian soldiers" who were stationed at Fort Meade and "used the fort's firing range without complaint of its proximity to Bear Butte."

This point is "absurd," said noted historian and attorney Vine Deloria Jr.

Deloria, who is Standing Rock Sioux and the author of more than two dozen books, said: "People serving in a foreign army are hardly the spiritual leaders of a country."

Lee claims that Bear Butte wasn't sacred to the Lakota "until after the butte was established as a state park in 1962." This is untrue, as historians worth their salt know and have documented, and as representatives of the Cheyenne River, Oglala and other Sioux tribes have been saying clearly and publicly in connection with the proposed shooting range.

He falsely claims that the Cheyenne "religion originated there." Tsistsistas Prophet Sweet Medicine received visions, medicines and instructions at Bear Butte that dramatically changed societal and ceremonial order, but Cheyenne religion existed for thousands of years before that time.

Lee also misperceives the history that is unfolding now, wrongly stating that "no objections to the proposed firing range in the vicinity of Bear Butte have come from the Cheyenne, who have been making pilgrimages to their sacred shrine for generations." Cheyenne leaders are clearly saying that the shooting range project would impede religious freedom and other rights.

Holy Mountain has been standing for more than 500 million years. It has taken the white man a little over a century to bring her to this point of endangerment. For more than 50 of those years, the federal government tried, but failed, to keep Indians away from Bear Butte. Today, it seems that developers and government agents are trying to take the mountain away from the Indians.

Bear Butte is strong and they will fail in this, too.

Suzan Shown Harjo, Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee, is president of the Morning Star Institute in Washington, D.C., and a columnist for Indian Country Today.

http://www.indiancountry.com/content.cfm?id=1046104233

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)