Cheyenne and Arapaho Revisited' at Denver March

Posted: March 31, 2008

by: Carol Berry

Click to Enlarge

Photo by Carol Berry -- Quinton Roman Nose, director of the education department at Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College

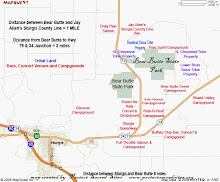

DENVER - The northern and southern bands of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal nations came together March 21 at the Denver March Pow Wow in a historic meeting termed ''Cheyenne and Arapaho Revisited.'' The event was the brainchild of Quinton Roman Nose, director of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College education department. ''We decided it was time we reasserted our right to our tribal knowledge, to teach it to our children,'' said Henrietta Mann, interim president of the tribal college located in Weatherford, Okla. She called the meeting a ''coming together.'' ''We are here as the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe of Oklahoma. We are here as the Northern Arapaho of Wyoming. We are here as the Northern Cheyenne from Montana. And as the Gros Ventre [a closely affiliated tribe] from Montana,'' she said. ''What a wonderful meeting.'' Northern and southern bands of the tribes separated in the mid-19th century with the incursion of increasing numbers of white settlers in the West and because of aggression on the part of the U.S. military. Denver - particularly the Cherry Creek and Denver International Airport areas - is in the original territory of the Cheyenne and Arapaho and is ''the land our ancestors walked on,'' Mann said in a keynote address. ''We're attached to this land every bit as much as plants that grow on this Earth.'' The conference, a first, drew more than 100 tribal members from Oklahoma, reservation areas of Wyoming and Montana, and elsewhere. In addition to the tribal college, sponsors included the education departments of Chief Dull Knife College in Montana and Wind River Tribal College in Wyoming, whose interim president, Marlin Spoonhunter, urged listening to the ''way of our ancestors, because they never gave up.'' Arapaho children may know their language early in life, but it is gradually lost in the public school system. ''One thing that kept the tribes together was the language,'' he said. ''We have a lot of work ahead of us.'' Bear Butte, a mountain near Sturgis, S.D., on the periphery of the Black Hills, was the topic of a presentation by Mann and her daughter, Montoya Whiteman, Cheyenne-Arapaho, associate director of training and technical assistance with the First Nations Development Institute in Longmont, Colo. They stressed the preservation of Bear Butte as a sacred site because it is the origin of Cheyenne culture, language and values, although today it is ''desecrated and violated.'' Mann recounted the story of Sweet Medicine, born to a virgin and left as a baby in what was described as reeds. He was said to have been raised by an old woman and banished from the tribe after a crime of violence. After four years, he emerged from present-day Bear Butte preceded by a powerful spirit who burned sweetgrass to purify the world. Cheyenne traditional tribal government, military societies, code of law, rules of conduct and prophecies are attributed to him. Holy earth spirits of Bear Butte designed the Cheyenne way, and ''all that is culturally Cheyenne originated there,'' she said. ''The mountain protects us.'' Bear Butte, a South Dakota state park and national landmark, is also sacred to Sioux nations as well as to the Kiowa, Arapaho and others, she said. ''It is a spiritually generous place.'' Human artifacts from 10,000 years ago have been found on Bear Butte, which is the source of ceremonial paints and animal life. Despite powerful storms, it is ''a peaceful and serene place'' for Cheyenne people who ''live in a spirit-filled world,'' she said. Whiteman said contemporary threats to the sanctity of Bear Butte include economic development, various types of pollution, human desecration and danger to animals. Threats to religious freedom on the mountain include the sound of gunfire from a nearby shooting range and noise from human activity that disturbs those engaged in prayers and vigils that require silent surroundings. The annual motorcycle rally in Sturgis that attracts thousands of bikers from across the United States is a major source of income for the area, so it has been difficult to enact protections for Bear Butte that could threaten income from the noisy event, she said. Nevertheless, South Dakota Gov. Mike Rounds has proposed a perpetual easement around Bear Butte to protect against development there, she said, urging interested people to contact the governor, Meade County commissioners, State Sen. Theresa Two Bulls or the organizations that are working to assist preservation. Those organizations include the South Dakota Peace and Justice Center, the Intertribal Coalition to Defend Bear Butte, Lakota Action Network, Bear Butte International Alliance, the Association of Christian Churches of South Dakota, the Seventh Generation Fund and the Indian Law Resource Center. ''Do that for your children,'' she said, ''because they're the ones that are going to have to carry the charge of protecting Bear Butte.'' Other sessions in the two-day conference covered language, tribal surveys, and oral and written history.http://www.indiancountry.com/content.cfm?id=1096416933

Wednesday, April 2, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment