Alone on S.D. prairie, surrounded by controversy

Seth Tupper The Daily Republic

Published Saturday, October 04, 2008

If other mountains surrounded it, Bear Butte might not be remarkable.

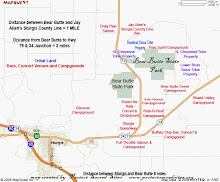

But Bear Butte is not surrounded by mountains. It is surrounded, quite starkly, by the prairie. The incongruity of the butte has made it a landmark recognized for its beauty and, by some, for its spiritual value. Prayer cloths and tobacco pouches tied to trees are evidence of the spiritual ceremonies that American Indians still conduct there.

The blessing of Bear Butte’s geographic isolation is also something of a curse. Exposed as it is by the surrounding landscape, the butte is viewed by some as vulnerable to development fueled by the motorcycle rally that roars annually into Sturgis, less than 10 miles down the road.

BEAR BUTTE STANDS alone on the prairie just outside of Sturgis. The mountain is a popular site for tourists and American Indians who practice religion there, but also is being hemmed in by private ownership. A proposed easement could help reverse that, but it won’t likely be paid for with state money, despite suggestions from Gov. Mike Rounds to do so.

RELATED CONTENT

Seth Tupper Archive

Last winter, Gov. Mike Rounds suggested pairing $250,000 of state money with $344,000 in private donations and a $594,000 federal grant to purchase an easement on private land adjacent to Bear Butte State Park. His goal was preventing development near the mountain.

State legislators declined to provide an appropriation for the proposal, and it languished out of the public eye until last week’s meeting of the Legislature’s Department of Game, Fish and Parks Review Committee in Pierre.

Some legislators on that panel said the state should not be involved in holding or funding an easement at Bear Butte. No formal action was taken by the committee, but GF&P Secretary Jeff Vonk said later during an interview that the message was clear. He now sees no chance of securing state funding for an easement.

“I don’t expect that we’ll be asking for state funds,” Vonk said in reference to the next legislative session, which begins Jan. 13. “I think it’s really up to a question about whether there’s some other entity that wants to step forward and provide funding.”

Vonk said he is not currently in talks with any such entity. Potential candidates could include national and international organizations like The Conservation Fund or The Nature Conservancy, he said, or local or regional groups interested in protecting Bear Butte.

The onus, apparently, will be on individuals to prevail upon such groups.

“We’ve got it on our list of potential projects,” Vonk said, “but I can’t tell you we’re out spending a lot of time beating the bushes to find funding sources.”

Gov. Rounds said his approach to the issue will depend on the state budget, which so far is not looking good.

“The early indications are that I’m going to have to scrape real hard just to make ends meet,” Rounds told The Daily Republic. “At the same time, if someone comes up with a foundation or someone like that comes up with the funds, I’d still be very supportive of a well-written lease that would protect the beauty of that land.”

Private vs. public

Bear Butte, called Mato Paha by Lakota Sioux Indians, is so named because of its resemblance to a bear sleeping on its side. The butte is actually a mountain formed by an unexploded volcano.

The elevation of Bear Butte’s peak, which is accessible by a hiking trail, is 4,422 feet above sea level. A state park visitors’ center at the foot of the mountain attracts about 40,000 people annually, and a small herd of bison roams nearby. The Black Hills can be seen in the distance.

Maj. George A. “Sandy” Forsyth encountered the Butte from the south in 1874 during the return trip of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s Black Hills Expedition. Forsyth wrote that, “Compared with the hills in the range, it is a pigmy, being only 1,140 feet above the level of the plains; but, standing alone as it does, it looms up quite grandly, especially when first seen by parties approaching the hills on this side.”

Today, most of Bear Butte is state-owned and designated as a state park. Some of the surrounding area is tribally owned. A portion of the mountain itself, and the rest of the area immediately surrounding it, is privately owned.

If an easement were established on privately owned land near the Butte, the landowner would retain ownership and rights to use the land for agricultural purposes. As part of the easement agreement, the landowner could not allow the land to be developed for commercial or residential purposes.

The term of the easement would be indefinite. It would remain in effect until such time as the state no longer wants it, much in the way railroad easements remain in effect until the tracks are no longer utilized.

A question of focus

Some legislators oppose a state-involved easement near Bear Butte because they don’t want the state tying up privately owned land for future generations.

Rep. Thomas Brunner, R-Nisland, who said he can see Bear Butte from his home window, is one of those legislators. He said easements only restrict landowner rights and provide no real rights for the public, because the land cannot be hunted or otherwise used by visitors.

“It serves no benefit in my mind,” Brunner said at last week’s committee meeting, “but quite the opposite, it prevents any practical use of this land.”

Vonk and Gov. Rounds disagree. They think an easement would provide the benefit of a protected “viewshed” for visitors to Bear Butte State Park. An easement would also keep the land privately owned and avoid perceptions of a government land grab, Vonk said.

“I think we’re looking at this in more of a narrow focus,” he told the legislative committee last week, “and I think a bigger focus would generate the public benefit that’s intended.”

Rep. Brunner said that despite his objections regarding easements, his main objection is the state’s involvement. He acknowledged, apparently reluctantly, that he would not oppose a privately held and funded easement at Bear Butte.

Rounds said the reason for having state money and involvement in an easement is to protect the state’s interest in its park.

“If the state has some money in it, we can kind of lay out the terms as to how the easement might be put together,” Rounds said. “If you don’ t have the dollars in it, in many cases you’re kind of outside the discussion.”

Motivations

Another objection to state-involved easements at Bear Butte is grounded in the doctrine of the separation of church and state.

State Rep. Betty Olson, who hails from the remote, far-northwestern corner of the state, believes the state-involved easement proposal would unconstitutionally involve the state in a religious matter.

Article VI, Section 3 of the state constitution states that no preference shall be given by law “to any religious establishment or mode of worship. No money or property of the state shall be given or appropriated for the benefit of any sectarian or religious society or institution.”

“The sole reason for the easement,” Olson said in an interview this week, “is to protect the Indians’ right to worship on Bear Butte, and I don’t think that’s a legitimate use of taxpayer dollars.”

Vonk disagrees. He said the public, via state government, has a significant investment in Bear Butte and should protect that investment.

“We acknowledge certainly that Bear Butte is an important cultural area for American Indians,” Vonk said. “It’s also a state park, and our motivations are basically to provide protection to a public resource that all of our citizens have ownership in.”

Without legislative support, the protection of Bear Butte as a public resource may now be truly a responsibility of the public.

Vonk said the GF&P has scaled back its easement proposal and is focusing on a smaller piece of land on the mountain’s southwest side. The proposed easement area includes the chunk of the mountain that is not within the park boundaries, and some additional land stretching out to nearby state Highway 79. The landowner is agreeable to an easement, Vonk said, but is not willing to sell the property outright.

The parcel is about 250 acres, and the cost to purchase an easement on the land is estimated to be $350,000. Vonk believes some federal grant money will be available, but if the easement is going to be secured it will require private groups and citizens to raise money and possibly volunteer to hold the easement.

‘Some respect’

There are people who are working to protect Bear Butte, but their efforts could be described as loosely organized.

Among them is Tamra Brennan, who lives near Bear Butte and identifies herself as a Cherokee tribal member. She runs Protect Bear Butte, an offshoot of Protect Sacred Sites. Both organizations are grassroots in nature and lack official nonprofit status.

Protect Bear Butte’s activism has so far taken the form of public information campaigns. Group members e-mailed thousands of bikers prior to this year’s Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and handed out fliers at the event. The intent was to educate bikers about the sacred nature of the mountain.

“All we’re asking is if bikers come to the area, please use some respect,” Brennan said.

Brennan also has argued against development near Bear Butte, including plans for bars or other biker-focused businesses in the mountain’s immediate vicinity.

She and others fear, however, that the privately owned land around Bear Butte could be sold at any time and converted to any use.

“We could have another ‘World’s Largest Biker Bar’ directly across from Bear Butte, or even at the base of Bear Butte,” Brennan said.

Brennan said she has hiked to the top of Bear Butte many times. She thinks that if everybody involved in the debates about development around Bear Butte would take time to make the hike, the mountain would win them over.

“It’s a very powerful and spiritual place,” she said. “Anybody that doesn’t feel that, it just doesn’t make any sense.”

Rep. Olson, who opposed the easement, has been to the summit. She thinks the mountain is worth protecting, but said it is sufficiently protected by the park designation.

“There’s nobody who’s going to be digging a hole in the top of it or trying to tear it down or anything.”

http://www.mitchellrepublic.com/articles/index.cfm?id=29395§ion=news&freebie_check&CFID=96608354&CFTOKEN=40203313&jsessionid=8830deefb31e73446347

Friday, October 3, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment